Playbook for Running Sprints

If you are reading this piece in 2020 as a member of an engineering/cross-functional team, chances are that the team you are on uses some mix of waterfall, scrum and kanban principles for planning. But what does that mix look like? Is it working well for the team, or is it getting in the way of product development?

This article attempts to describe the "Ideal Sprint" or well, to put my thoughts down on what I've seen working well during my years as a software engineer and engineering manager.

Characteristics of Efficient Sprints

When I think about what makes sprints efficient, my thoughts are usually around these goals:

- The team always works on the most important stories. The most important work item can be defined broadly, but it can be the features that provide the most value for the customer or eliminating the tech debt that slows the team down.

- We have a healthy feedback culture on the team. Retrospectives are about discussing real problems and solutions for them.

- The team has estimations to ensure that we have a rough idea of when given projects are shipping.

- We have to ensure that there are no single points of failure on the team: multiple engineers should work on the same problems. This enables the team to work together: stories are not created for individuals, but for the group as a whole.

The framework

Let's start with a few rough definitions:

- The backlog is a semi-prioritized list of things that the team eventually wants to work on. Stories in the backlog may never get picked up, depending on priorities.

- Stories are work items that never take more than a week to accomplish. The time limit on them is critical. It helps teams with story sizing.

- During backlog refinement (or grooming), the whole team gets together to estimate stories using story points and prioritize the backlog taking the new stories and potentially shifting priorities into account.

- Story points are abstract units for measuring complexity. During backlog refinement, story points are assigned to new stories.

- The scrum master is the team member responsible for running the scrum meetings and helping unblock engineers on the team. The team can decide to rotate the scrum master every few sprints.

- Velocity is the sum of the story points the team takes on and finishes in any given sprint.

Now that we got most of the definitions out of the way, let's take a look at what processes the team follows and the lifecycle of stories.

Meetings and their purpose

Backlog refinement

Frequency: once every two weeks Length: 30 mins Owner: scrum masterEvery other week, the team has a backlog refinement session. The goal of this meeting is to estimate any new stories and change their order (priority) in the backlog. To get the most out of this session, the scrum master has to prepare: they need to know what stories will be estimated, and if the stories have enough context so the team can estimate them. If not, the scrum master has to ask for clarification before the meeting takes place. If by the time of the backlog refinement meeting there is not enough information to estimate a story, the team skips the story.

The estimation of a story may go something like this:

- The scrum master summarizes the story on hand in less than a minute and asks if anyone on the team has questions or can proceed to estimation.

- If the team has questions, we first discuss them and ensure that everyone has the same understanding of the work item.

- The group estimates the story by anonymously voting using tools like Hatjitsu or Scrum Poker.

- If there was a close to a unanimous vote, the scrum master picks the estimation and assigns it to the story.

- Useful phrases: "Is everyone okay going with a 3?" or "Seems like an even split between 2 and 3, let's go with a 3."

- In case of a big spread, the scrum master asks the team who wants to speak up and reason why they thought the given story should be estimated the way they estimated it. After some discussion, the team re-estimates the story.

- Useful phrases: "Who'd like to speak up and let us know why they voted the way they did?" or "Jane, as someone who worked on this feature recently, what are your thoughts?"

When a team adopts estimation that never did it before, it may be helpful to think about story points as time estimations: one story point for one day of work should do. After a few sprints, the team can slowly move away from the time estimation and start trying to assign story points based on each story's complexity.

Retrospective & Sprint planning

Frequency: once every two weeks Length: 60 mins Owner: scrum masterThis meeting consists of two parts. The first part is a retrospective for the sprint the team is about to close and the goal of this part is to give kudos and discuss problems. The group spends the first few minutes highlighting what went well and what needs to be improved by collaborating on a shared document. After five minutes, or when folks stop typing, the scrum master starts going through the items, and the team briefly discusses them. One of the most important parts of this meeting is to discuss what needs to be improved and assigning clear owners of the action items.

The second part of this session is sprint planning, with the goal to understand the team's velocity, and what will be the main focus for the next sprint.

You could follow an agenda similar to this:

- Go through the current sprint's open stories, and make sure they are up-to-date. Move the in progress and unstarted stories to the next sprint.

- Take a look at holidays and planned vacations for the next two weeks. This both helps with capacity planning and ensures team members know when their peers will be out.

- Agree on the targeted velocity for the next sprint by looking at past sprints and considering planned vacations.

- If there are new stories that will need to be included in the next sprint, do a quick estimation session.

- Discuss what the next sprint priorities should be and start pulling in stories. Decide if the stories spilled over from the previous sprint are still a high priority, or if they should be moved out. A key input for priorities should come from the prioritized backlog: a big chunk of the capacity should be filled in with stories from the top of the backlog.

- Useful phrases: "It seems like we are close to our target velocity - did we miss anything important that we want to work on in the next sprint?"

You can use this template to keep track of retros and sprint plannings. The planning section is filled out during sprint planning, and the retro section is filled out during the Retrospective meeting in two weeks. So in practice, you'll edit two of these documents during this meeting, one for the past sprint, and one for the next one.

Standups

Frequency: twice every week / every day Owner: scrum masterIf possible, try having standups in-person or through Zoom. In this new virtual reality introduced because of COVID, it’s important to have human connections as much as possible. When doing standups face-to-face, I found this framework to work best:

- The scrum master shares their screen, looking at the scrum board,

- Every individual on the team provides a 1-minute update,

- If topics need further discussion, the parking lot is used at the end of the standup. Attendance for this part is optional.

If you are part of a globally distributed team, you can try doing standups over Slack twice a week.

- Standups provided through Slack are easier to consume and follow up on: using threads, we can have longer conversations without taking up time from the entire team.

- Standups tend to be more structured if provided through Slack. Every Tuesday and Thursday, a Slack bot can remind people to provide their standup using a template, reminding folks what should be included in their update.

Putting it all together

I found it best to start sprints on Mondays and close them the next Friday. This way, calendar weeks directly maps to sprints, without any cognitive overhead (like starting sprints on Wednesday).

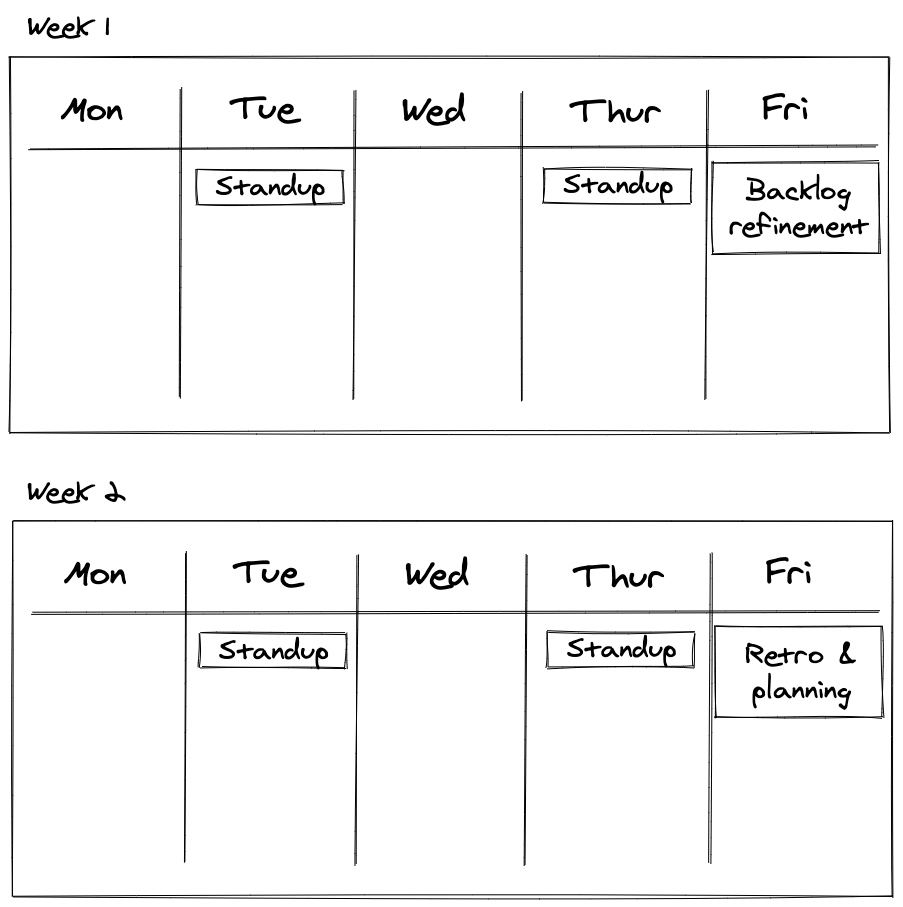

With this in mind, a calendar for a sprint for a scrum team may look like this:

The lifecycle of a story

Now that we covered the definitions and the meetings involved in efficient sprints let's also recap the lifecycle of stories.

Every story is created equal - we do not differentiate between bugs, feature work, or discovery (spike). They go through the same estimation and prioritization sessions. This way, the team can better plan each sprint the amount of work they can take on.

- The story/bug/spike is created and placed at the bottom of the backlog

- In case of bugs coming from customers/other teams, you probably want to set up a way to triage them more frequently, so they don't sit in the backlog for a week. This could be a rotating responsibility, as a support engineer role, or can be done by the scrum master.

- The team meets for backlog refinement and sprint planning to look at new items, estimate and prioritize them.

- The story gets pulled into one of the next sprint (or will sit in the backlog for eternity).

Sprints & planning cycles

Okay, okay, but how does this process fit into quarterly/semi-annual planning cycles?

Ideally, in your planning cycles, you set goals using OKRs. These goals will be the primary inputs for your prioritization discussions during sprint planning and backlog refinement.

Another question that can also come up when following this framework is how the team will meet deadlines?

Taking a look at the team's average velocity and summing up the estimations for stories required for a feature or release gives a relatively accurate picture of when a team can ship a feature. Estimations also empower the engineering team to help decide what parts could be cut to make a deadline.

I realize that these answers barely scratch the surface, but they deserve an article of their own. Be on the lookout, I am planning to work on them next!

Conclusion

By following this framework, you can create a streamlined sprint planning process that only adds less than an hour of meeting overhead to the team's weekly schedule: the backlog refinement takes only half an hour. The joint retrospective and sprint planning meeting an hour.

I am thrilled that we created this sprint planning framework - it saves the teams following it countless hours spent in meetings, and helps them keep focused. It also reduces the friction caused by annual, semi-annual, or quarterly plannings.

Special thanks go to Chase Starr, who contributed a lot to the framework I described above!